As you look around the dog park, you're probably seeing at least one dog who has cruciate issues

it's incredibly common

We'll focus on the cranial cruciate ligament here because it's the one (of two cruciates) that is most affected. It’s called the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in people … and we often call it that too.

Before we go further, note the two terms: cranial cruciate ligament disease and cranial cruciate rupture. Same same but slightly different:

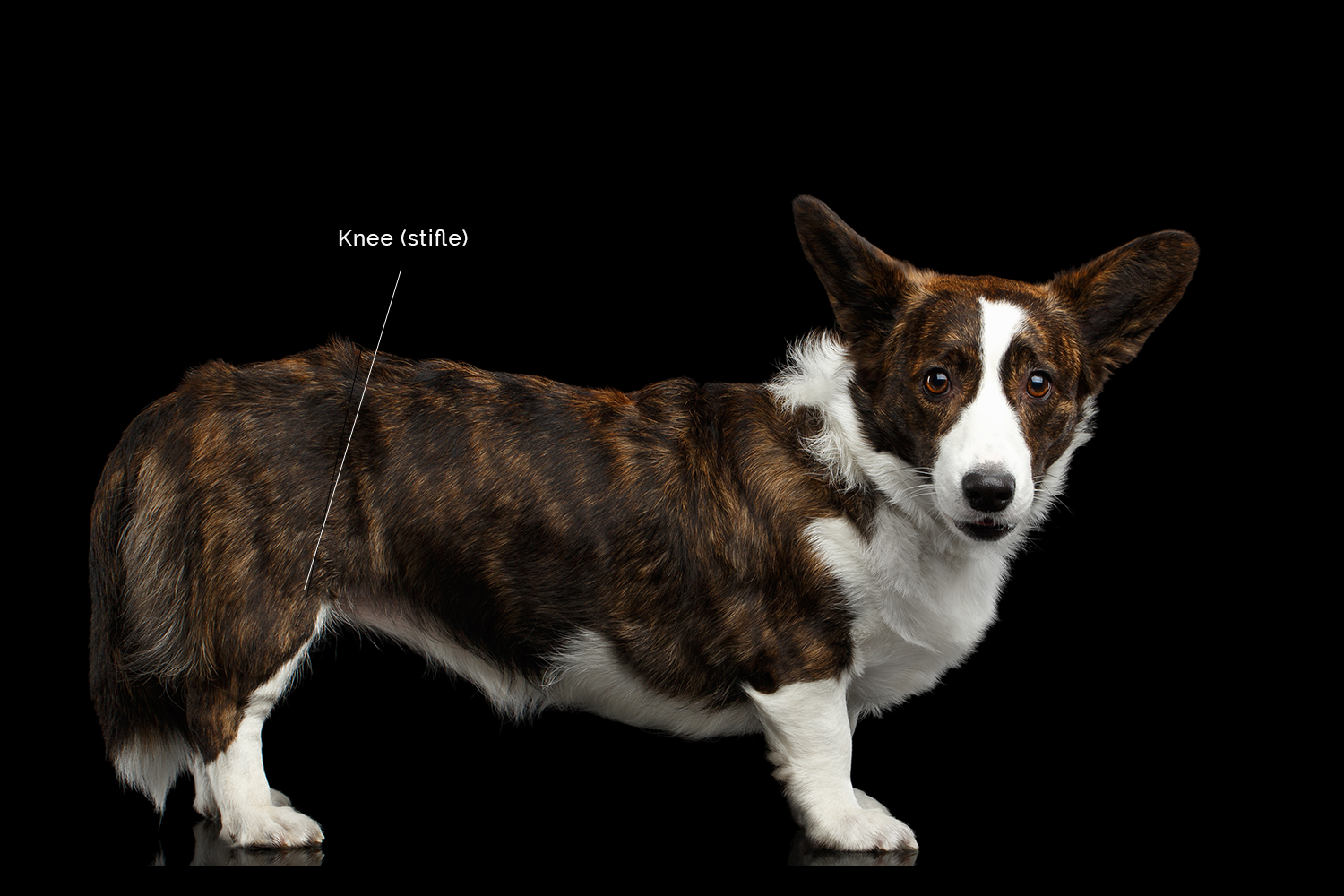

Cruciate disease describes sudden or progressive failure of the cranial cruciate ligament causing partial or complete instability of the knee (stifle) joint

Cruciate rupture refers to tearing of the cranial cruciate ligament – tearing may be partial or complete. A tear is also called a sprain

Cranial cruciate rupture is the most common cause of hind limb lameness in dogs. In fact, if your dog suddenly starts limping/holding up a back leg, there's a higher chance of a cranial cruciate ligament tear than anything else. Cruciate rupture is a major cause of knee arthritis.

Where and what are cruciate ligaments?

The cruciate ligaments are in the knee. The knee is a complex joint is made up of:

the bottom end of the thigh bone (femur)

the top part of the shin bone (tibia)

a couple of small bones at the back of the knee (fabellae)

the kneecap (patella)

cartilage pads (menisci)

multiple ligaments that hold the whole thing together

Ligaments are fibrous bands that connect bones or cartilages together (as opposed to tendons, which attach muscles to bones). There are two cruciate ligaments in each knee: the cranial (or anterior) cruciate and the caudal (or posterior) cruciate. They connect from one side of the femur on the top to the opposite site of the tibia on the bottom. They cross over in the middle – hence the name cruciate, which means cross. The cranial cruciate attaches the front of the tibia to the back of the femur. And the caudal cruciate attaches the other way.

The cruciate ligaments prevent the two relatively flat surfaces of the femur and tibia from sliding back and forth. If the cranial cruciate ruptures completely, the tibia can slip forward from under the femur.

The vet school at the University of Edinburgh (know charmingly as 'The Dick Vet'), has produced an excellent YouTube video (see below) explaining what the cranial cruciate ligament does, what happens when it tears and some of the surgical techniques used to stabilise the knee.

What causes cruciate ligament rupture?

There are several different scenarios for ruptured cruciate ligaments.

The (young) athletic dog

This is a similar scenario to the ALF footie player. A fit dog lands awkwardly after leaping for a frisbee or turns sharply when running flat out or takes a wrong step while playing roughly... anyway, something vigorous... and the ligament goes ping.

There are several breeds that are more prone to this: Labradors, Golden Retrievers, Rotties, Mastiffs and American Staffies.

The older, large breed (and often overweight) dog

These dogs' cruciate ligaments can become weaker or stretched over time leading to partial tears. These partial tears cause some inflammation and pain, but there may not be dramatic lameness until the ligament snaps completely. It doesn't take much to rupture these weakened ligaments. Simple activities such as getting out of bed or going down some steps may be all that's needed.

In this scenario, we often see the other knee having the same problem within a year.

The smaller breed dog with dodgy knees

Smaller breed dogs frequently have a condition called patella luxation, which is where the kneecap (patella) moves in and out of the patella groove. Even if the patella luxation is mild, the altered position places stress on the cranial cruciate ligament and may lead to rupture.

How do I know if my dog has a cruciate ligament tear?

Cruciate ligament tears cause lameness. This may be acute lameness as soon as the tear occurs or chronic lameness due to instability or arthritis.

when the tear occurs

If your dog tears a cranial cruciate ligament, he'll usually seem sore on the affected hind limb. He may walk or run on three legs, or use the leg but be noticeably limping. When standing, you might see that he sort of just touches the ground with his inner toe. There is usually some swelling, but it can be very difficult to detect unless your dog has slim legs with very short hair.

soon after the tear

If left alone, the lameness will usually reduce over a week or two. This doesn't mean that the tear is repairing, it just means that the acute inflammation is resolving. Unfortunately, arthritis may already be setting in. In some patients, we can see degenerative bone changes within 1–3 weeks of cruciate rupture.

Later on

Some dogs return to normal. Others may continue to be lame due to the knee being unstable and arthritic changes. Whether the lameness resolves or to what degree arthritic degeneration happens depends a lot on the size of the dog.

In an older study (which still stands), a group of dogs was studied for 6 months after cruciate rupture. At the end of 6 months, 85% of dogs weighing less than 15 kg regained near normal or improved function while only 19% of dogs over >15 kg regained near normal function. Both groups of dogs required at least 4 months to show maximum improvement.

How do vets diagnose cruciate rupture?

The way we detect a ruptured cruciate ligament is by detecting abnormal movement of the tibia in relation to the femur. The most common test performed in the drawer sign. If you watched The Dick Vet video, this is shown about 3 mins 45 secs in. The other test done is the tibial compression test (around 3 mins 14 secs). Some dogs really tense up at the vets and their tight muscles can sort of temporarily stabilise the knee. Sedation if often needed to get a really good feel. If the ligament is only partially torn, we might not detect abnormal movements.

We'll also be looking for signs of fluid swelling in the joint (called an effusion) and whether there is a firm swelling on the inner part of the knee. This is called a medial buttress and indicates that the rupture occurred a while ago.

Radiographs may be recommended, not necessarily to diagnose a rupture, but to rule out other causes of hind limb lameness (eg tibial crest avulsions, bone tumours) and to look for signs of arthritis. The degree of arthritis will affect the prognosis.

How is cruciate ligament rupture treated?

Initially, we want to reduce pain and inflammation. The most common treatment for that is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) such as meloxicam or carprofen. This may be all that's required for partial tears or small breed dogs. (Just a quick warning – don't use human medication for dogs unless you have discussed this with a vet)

If the ligament has completely ruptured, then the joint is unstable. So even if the acute pain and inflammation are under control, when your dog puts weight on the leg, the tibia will slip causing the knee to give way a bit. This is an unpleasant sensation and causes degenerative wear and tear on the cartilages.

While there is considerable controversy surrounding surgery for people with cruciate ligament rupture, the scientific evidence in dogs supports is more clearly in favour of surgery being benefiical.

cruciate surgery

There are three main surgical techniques used currently:

extracapsular repair (commonly known as the De Angelis technique or lateral suture technique) – which is the traditional surgical method for a ruptured cruciate. I can't explain this better than The Dick Vet video (4 minutes and 29 seconds)

tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO) – which was developed initially for larger dogs to change the angles of joint. And again, The Dick Vet video does a great job of explaining it

tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA) – is similar to the TPLO inasmuch as it changes angles. Once again, the video explains it better than I can!

Although I said there is less controversy about the benefits of cruciate surgery in dogs than in people, there is (endless) debate about which surgical procedure is better. Each one has pros and cons. The best way to decide is to have a discussion with Dr Craig Goode, who is the one who does this surgery at Elwood.

What is the post-op process?

A supportive dressing is usually placed after surgery. This holds the knee in a fairly fixed position, which can be a bit awkward for some dogs (especially low to the ground ones with bandy legs). This dressing will usually stay on for 3–7 days.

Pain relief is given before your pet wakes up from surgery and then continues as needed. We often use a combination of opioid pain patches and oral anti-inflammatory medication to ensure your pet is as comfortable as possible.

Unless your dog is already receiving them, we'll start a course of pentosan (Zydax®) injections to aid healing.

Generally, you should expect a 8–12 week recovery period:

during the first couple of weeks, confinement is needed and activity is restricted to just going out to the toilet (maybe with a supporting sling) – it's a good idea to have a crate or child's playpen ready for when your dog comes home after surgery

most dogs will be using the leg again within 10 days of the surgery (some take longer, up to around 3 weeks)

after the sutures are removed, you might want to consider hydrotherapy (eg sessions on an underwater treadmill)

by around 3–4 weeks, some short easy walking can be introduced – but no running, jumping or stairs

by 8–12 weeks exercise restriction can usually be lifted (depending on individual recovery)

If your dog has cruciate surgery with us, you will be given a handout that goes through what you need to do and what to expect, step-by-step.